History Of Eugenics on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of eugenics is the study of development and advocacy of ideas related to

Sir

Sir

In September 1903, an "Inter-departmental Committee on Physical Deterioration" chaired by Almeric W. FitzRoy was appointed by the government "to make a preliminary enquiry into the allegations concerning the deterioration of certain classes of the population as shown by the large percentage of rejections for physical causes of recruits for the

In September 1903, an "Inter-departmental Committee on Physical Deterioration" chaired by Almeric W. FitzRoy was appointed by the government "to make a preliminary enquiry into the allegations concerning the deterioration of certain classes of the population as shown by the large percentage of rejections for physical causes of recruits for the

eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

around the world. Early eugenic ideas were discussed in Ancient Greece and Rome. The height of the modern eugenics movement came in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.History

The eugenics was most famously expounded byPlato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, who believed human reproduction should be monitored and controlled by the state. However, Plato understood this form of government control would not be readily accepted, and proposed the truth be concealed from the public via a fixed lottery. Mates, in Plato's ''Republic'', would be chosen by a "marriage number" in which the quality of the individual would be quantitatively analyzed, and persons of high numbers would be allowed to procreate with other persons of high numbers. In theory, this would lead to predictable results and the improvement of the human race. However, Plato acknowledged the failure of the "marriage number" since "gold soul" persons could still produce "bronze soul" children. Plato's ideas may have been one of the earliest attempts to mathematically analyze genetic inheritance

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic informa ...

, which was later improved by the development of Mendelian genetics

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biology, biological Heredity, inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, an ...

and the mapping of the human genome

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as DNA within the 23 chromosome pairs in cell nuclei and in a small DNA molecule found within individual mitochondria. These are usually treated separately as the n ...

.

Other ancient civilizations, such as Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

and Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

, practiced infanticide

Infanticide (or infant homicide) is the intentional killing of infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children, its main purpose is the prevention of reso ...

through exposure and execution as a form of phenotypic selection. In Sparta, newborns were inspected by the city's elders, who decided the fate of the infant. If the child was deemed incapable of living, it was usually exposed in the ''Apothetae'' near the Taygetus

The Taygetus, Taugetus, Taygetos or Taÿgetus ( el, Ταΰγετος, Taygetos) is a mountain range on the Peloponnese peninsula in Southern Greece. The highest mountain of the range is Mount Taygetus, also known as "Profitis Ilias", or "Prophet ...

mountain. As of 2007, the dumping of infants near Mount Taygete has been called into question due to a lack of physical evidence. Anthropologist Theodoros Pitsios' research has found only bodies of adolescents up to the age of approximately 35.

Trials for babies included bathing them in wine

Wine is an alcoholic drink typically made from fermented grapes. Yeast consumes the sugar in the grapes and converts it to ethanol and carbon dioxide, releasing heat in the process. Different varieties of grapes and strains of yeasts are m ...

and exposing them to the elements. To Sparta, this would ensure only the strongest survived and procreated. Adolf Hitler considered Sparta to be the first " ''Völkisch'' State", and much like Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, naturalist, eugenicist, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biologist and artist. He discovered, described and named thousands of new sp ...

before him, praised Sparta for its selective infanticide policy.

The Twelve Tables of Roman Law, established early in the formation of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kin ...

, stated in the fourth table that deformed children must be put to death. In addition, patriarchs

The highest-ranking bishops in Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Catholic Church (above major archbishop and primate (bishop), primate), the Hussite Church, Church of the East, and some Independent Catholicism, Independent Catholic Chur ...

in Roman society

The culture of ancient Rome existed throughout the almost 1200-year history of the civilization of Ancient Rome. The term refers to the culture of the Roman Republic, later the Roman Empire, which at its peak covered an area from present-day Lo ...

were given the right to "discard" infants at their discretion. This was often done by drowning undesired newborns in the Tiber River

The Tiber ( ; it, Tevere ; la, Tiberis) is the third-longest river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where it is joined by the Riv ...

. Commenting on the Roman practice of eugenics, the philosopher Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

wrote that: "We put down mad dogs; we kill the wild, untamed ox; we use the knife on sick sheep to stop their infecting the flock; we destroy abnormal offspring at birth; children, too, if they are born weak or deformed, we drown. Yet this is not the work of anger, but of reason – to separate the sound from the worthless". The practice of open infanticide in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

did not subside until its Christianization

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

, which however also mandated ''negative'' ''eugenics'', e.g. by the council of Adge in 506, which forbade marriage between cousins.

Galton's theory

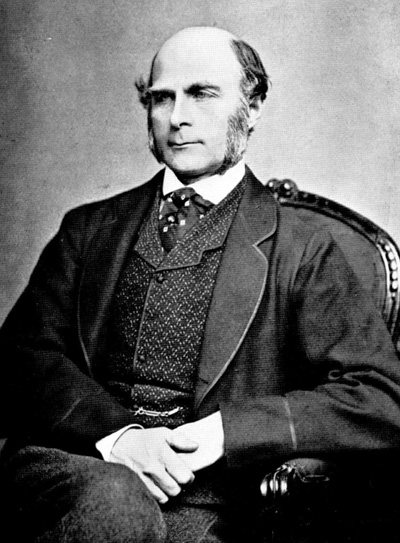

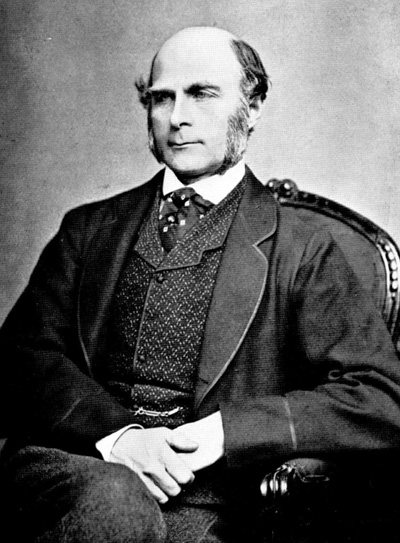

Sir

Sir Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton, FRS FRAI (; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911), was an English Victorian era polymath: a statistician, sociologist, psychologist, anthropologist, tropical explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist, proto- ...

(1822–1911) systematized these ideas and practices according to new knowledge about the evolution of man and animals provided by the theory of his half-cousin Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

during the 1860s and 1870s. After reading Darwin's ''Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'', Galton built upon Darwin's ideas whereby the mechanisms of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

were potentially thwarted by human civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

Ci ...

. He reasoned that, since many human societies sought to protect the underprivileged and weak, those societies were at odds with the natural selection responsible for extinction of the weakest; and only by changing these social policies could society be saved from a "reversion towards mediocrity", a phrase he first coined in statistics and which later changed to the now-common "regression towards the mean

In statistics, regression toward the mean (also called reversion to the mean, and reversion to mediocrity) is the fact that if one sample of a random variable is extreme, the next sampling of the same random variable is likely to be closer to ...

".

Galton first sketched out his theory in the 1865 article "Hereditary Talent and Character", then elaborated further in his 1869 book ''Hereditary Genius

''Hereditary Genius: An Inquiry Into Its Laws and Consequences'' is a book by Francis Galton about the genetic inheritance of intelligence. It was first published in 1869 by Macmillan Publishers. The first American edition was published by D. A ...

''. He began by studying the way in which human intellectual, moral, and personality traits tended to run in families. Galton's basic argument was "genius" and "talent" were hereditary traits in humans (although neither he nor Darwin yet had a working model of this type of heredity). He concluded since one could use artificial selection

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant m ...

to exaggerate traits in other animals, one could expect similar results when applying such models to humans. As he wrote in the introduction to ''Hereditary Genius'':

I propose to show in this book that a man's natural abilities are derived by inheritance, under exactly the same limitations as are the form and physical features of the whole organic world. Consequently, as it is easy, notwithstanding those limitations, to obtain by careful selection a permanent breed of dogs or horses gifted with peculiar powers of running, or of doing anything else, so it would be quite practicable to produce a highly gifted race of men by judicious marriages during several consecutive generations.Galton claimed that the less intelligent were more fertile than the more intelligent of his time. Galton did not propose any selection methods; rather, he hoped a solution would be found if social

mores

Mores (, sometimes ; , plural form of singular , meaning "manner, custom, usage, or habit") are social norms that are widely observed within a particular society or culture. Mores determine what is considered morally acceptable or unacceptable ...

changed in a way that encouraged people to see the importance of breeding. He first used the word ''eugenic'' in his 1883 '' Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development'', a book in which he meant "to touch on various topics more or less connected with that of the cultivation of race, or, as we might call it, with 'eugenic' questions". He included a footnote to the word "eugenic" which read:

That is, with questions bearing on what is termed in Greek, ''eugenes'' namely, good in stock, hereditary endowed with noble qualities. This, and the allied words, ''eugeneia'', etc., are equally applicable to men, brutes, and plants. We greatly want a brief word to express the science of improving stock, which is by no means confined to questions of judicious mating, but which, especially in the case of man, takes cognizance of all influences that tend in however remote a degree to give to the more suitable races or strains of blood a better chance of prevailing speedily over the less suitable than they otherwise would have had. The word ''eugenics'' would sufficiently express the idea; it is at least a neater word and a more generalized one than ''viriculture'' which I once ventured to use.In 1908, in ''Memories of my Life'', Galton stated the official definition of eugenics: "the study of agencies under social control that may improve or impair the racial qualities of future generations, either physically or mentally". This had been agreed in consultation with a committee that included the

biometrician

Biostatistics (also known as biometry) are the development and application of statistical methods to a wide range of topics in biology. It encompasses the design of biological experiments, the collection and analysis of data from those experimen ...

Karl Pearson

Karl Pearson (; born Carl Pearson; 27 March 1857 – 27 April 1936) was an English mathematician and biostatistician. He has been credited with establishing the discipline of mathematical statistics. He founded the world's first university st ...

. It was slightly at odds with Galton's preferred definition, given in a lecture to the newly formed Sociological Society at the London School of Economics

, mottoeng = To understand the causes of things

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £240.8 million (2021)

, budget = £391.1 millio ...

in 1904: "the science which deals with all influences that improve the inborn qualities of a race; also with those that develop them to the utmost advantage". The latter definition, which encompassed nurture and environment as well as heredity, was favoured by broadly left wing, liberal elements of the ensuing ideological divide.

Galton's formulation of eugenics was based on a strong statistical

Statistics (from German: ''Statistik'', "description of a state, a country") is the discipline that concerns the collection, organization, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of data. In applying statistics to a scientific, industria ...

approach, influenced heavily by Adolphe Quetelet

Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet FRSF or FRSE (; 22 February 1796 – 17 February 1874) was a Belgian astronomer, mathematician, statistician and sociologist who founded and directed the Brussels Observatory and was influential in introduc ...

's "social physics". Unlike Quetelet, however, Galton did not exalt the "average man" but decried him as mediocre. Galton and his statistical heir Karl Pearson

Karl Pearson (; born Carl Pearson; 27 March 1857 – 27 April 1936) was an English mathematician and biostatistician. He has been credited with establishing the discipline of mathematical statistics. He founded the world's first university st ...

developed what was called the biometrical approach to eugenics, which developed new and complex statistical models (later exported to wholly different fields) to describe the heredity of traits. However, with the rediscovery of Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel, Augustinians, OSA (; cs, Řehoř Jan Mendel; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was a biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinians, Augustinian friar and abbot of St Thomas's Abbey, Brno, St. Thomas' Abbey in Br� ...

's hereditary laws, two separate camps of eugenics advocates emerged. One was made up of statisticians, the other of biologists. Statisticians thought the biologists had exceptionally crude mathematical models, while biologists thought the statisticians knew little about biology.

Eugenics eventually referred to human selective reproduction with an intent to create children with desirable traits, generally through the approach of influencing differential birth rates

Differential may refer to:

Mathematics

* Differential (mathematics) comprises multiple related meanings of the word, both in calculus and differential geometry, such as an infinitesimal change in the value of a function

* Differential algebra

* ...

. These policies were mostly divided into two categories: ''positive eugenics'', the increased reproduction of those seen to have advantageous hereditary traits; and ''negative eugenics'', the discouragement of reproduction by those with hereditary traits perceived as poor. Negative eugenic policies in the past have ranged from paying those deemed to have bad genes to voluntarily undergo sterilization, to attempts at segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

to compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, is a government-mandated program to involuntarily sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's capacity to reproduce, and is usually done throug ...

and even genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Latin ...

. Positive eugenic policies have typically taken the form of awards or bonuses for "fit" parents who have another child. Relatively innocuous practices like marriage counseling

Couples therapy (also couples' counseling, marriage counseling, or marriage therapy) attempts to improve romantic relationships and resolve interpersonal conflicts.

History

Marriage counseling originated in Germany in the 1920s as part of the eu ...

had early links with eugenic ideology. Eugenics is superficially related to what would later be known as Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in We ...

. While both claimed intelligence was hereditary, eugenics asserted new policies were needed to actively change the status quo towards a more "eugenic" state, while the Social Darwinists argued society itself would naturally "check" the problem of "dysgenics

Dysgenics (also known as cacogenics) is the decrease in prevalence of traits deemed to be either socially desirable or well adapted to their environment due to selective pressure disfavoring the reproduction of those traits.

The adjective "dysgeni ...

" if no welfare policies were in place (for example, the poor might reproduce more but would have higher mortality rates).

Charles Davenport

Charles Davenport

Charles Benedict Davenport (June 1, 1866 – February 18, 1944) was a biologist and eugenics, eugenicist influential in the Eugenics in the United States, American eugenics movement.

Early life and education

Davenport was born in Stamford, Co ...

(1866-1944), a scientist from the United States, stands out as one of history's leading eugenicists. He took eugenics from a scientific idea to a worldwide movement implemented in many countries. Davenport obtained funding from the Carnegie Institution, to establish the Station for Experimental Evolution at Cold Spring Harbor in 1904 and the Eugenics Records Office in 1910, which provided the scientific basis for later Eugenic policies such as enforced sterilization. He became the first President of the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations The International Federation of Eugenic Organizations (IFEO) was an international organization of groups and individuals focused on eugenics. Founded in London in 1912, where it was originally titled the Permanent International Eugenics Committee, i ...

(IFEO) in 1925, an organization he was instrumental in building. While Davenport was located at Cold Spring Harbor and received money from the Carnegie Institute of Washington, the organization known as the Eugenics Record Office

The Eugenics Record Office (ERO), located in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, United States, was a research institute that gathered biological and social information about the American population, serving as a center for eugenics and human heredity ...

(ERO) started to become an embarrassment after the well-known debates between Davenport and Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the movements known as historical ...

. Instead, Davenport occupied the same office and the same address at Cold Spring Harbor, but his organization now became known as the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories, which currently retains the archives of the Eugenics Record Office. However, Davenport's racist views were not supported by all geneticists at Cold Spring Harbor, including H. J. Muller, Bentley Glass, and Esther Lederberg

Esther Miriam Zimmer Lederberg (December 18, 1922 – November 11, 2006) was an American microbiologist and a pioneer of bacterial genetics. She discovered the bacterial virus λ and the bacterial fertility factor F, devised the first impl ...

.

In 1932, Davenport welcomed Ernst Rüdin

Ernst Rüdin (19 April 1874 – 22 October 1952) was a Swiss-born German psychiatrist, geneticist, eugenicist and Nazi, rising to prominence under Emil Kraepelin and assuming the directorship at the German Institute for Psychiatric Rese ...

, a prominent Swiss eugenicist and race scientist, as his successor in the position of President of the IFEO. Rüdin, director of the ''Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft'' (German Research Institute for Psychiatry, located in Munich), a Kaiser Wilhelm Institute

The Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science (German: ''Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften'') was a German scientific institution established in the German Empire in 1911. Its functions were taken over by ...

, was a co-founder (with his brother-in-law Alfred Ploetz

Alfred Ploetz (22 August 1860 – 20 March 1940) was a German physician, biologist, Social Darwinist, and eugenicist known for coining the term racial hygiene (''Rassenhygiene''), a form of eugenics, and for promoting the concept in Germany.

Ea ...

) of the German Society for Racial Hygiene

The German Society for Racial Hygiene (german: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Rassenhygiene) was a German eugenic organization founded on 22 June 1905 by the physician Alfred Ploetz in Berlin. Its goal was "for society to return to a healthy and bloomi ...

. Rudin's half-brother Ploetz recommended a "racial hygiene

The term racial hygiene was used to describe an approach to eugenics in the early 20th century, which found its most extensive implementation in Nazi Germany (Nazi eugenics). It was marked by efforts to avoid miscegenation, analogous to an animal ...

" system in which panels of physicians decided whether to grant individuals citizenship

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

or euthanasia

Euthanasia (from el, εὐθανασία 'good death': εὖ, ''eu'' 'well, good' + θάνατος, ''thanatos'' 'death') is the practice of intentionally ending life to eliminate pain and suffering.

Different countries have different eut ...

. Other prominent figures in eugenics who were associated with Davenport included Harry Laughlin

Harry Hamilton Laughlin (March 11, 1880 – January 26, 1943) was an American educator and eugenicist. He served as the superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office from its inception in 1910 to its closure in 1939, and was among the most a ...

(United States), Havelock Ellis

Henry Havelock Ellis (2 February 1859 – 8 July 1939) was an English physician, eugenicist, writer, progressive intellectual and social reformer who studied human sexuality. He co-wrote the first medical textbook in English on homosexuality in ...

(United Kingdom), Irving Fischer

Irving Fisher (February 27, 1867 – April 29, 1947) was an American economist, statistician, inventor, eugenicist and progressive social campaigner. He was one of the earliest American neoclassical economists, though his later work on debt def ...

(United States), Eugen Fischer

Eugen Fischer (5 July 1874 – 9 July 1967) was a German professor of medicine, anthropology, and eugenics, and a member of the Nazi Party. He served as director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, ...

(Germany), Madison Grant

Madison Grant (November 19, 1865 – May 30, 1937) was an American lawyer, zoologist, anthropologist, and writer known primarily for his work as a eugenicist and conservationist, and as an advocate of scientific racism. Grant is less noted f ...

(United States), Lucien Howe

Lucien Howe (September 18, 1848 – December 27, 1928) was an American physician who spent much of his career as a professor of ophthalmology at the University at Buffalo. In 1876 he was instrumental in the creation of the Buffalo Eye and Ear Infi ...

(United States), and Margaret Sanger

Margaret Higgins Sanger (born Margaret Louise Higgins; September 14, 1879September 6, 1966), also known as Margaret Sanger Slee, was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger popularized the term "birth control ...

(United States, founder of a New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

health clinic that later became Planned Parenthood

The Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc. (PPFA), or simply Planned Parenthood, is a nonprofit organization that provides reproductive health care in the United States and globally. It is a tax-exempt corporation under Internal Reve ...

). Later Sanger commissioned the first birth control pill

The combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP), often referred to as the birth control pill or colloquially as "the pill", is a type of birth control that is designed to be taken orally by women. The pill contains two important hormones: progest ...

.

United Kingdom

Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

", and gave its Report to both houses of parliament in the following year. Among its recommendations, originating from professor Daniel John Cunningham

Daniel John Cunningham M.D., D.C.L., LL. D. F.R.S., F.R.S.E. F.R.A.I. (15 April 1850 – 23 July 1909) was a Scottish physician, zoologist, and anatomist, famous for ''Cunningham's Text-book of Anatomy'' and ''Cunningham's Manual of Prac ...

, were an anthropometric survey of the British population. The Catholic church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

was opposed to eugenics, as illustrated in the writings of Father Thomas John Gerrard.

Eugenics was supported by many prominent figures of different political persuasions before World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

(and as positive eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

after the War), including: Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

economists William Beveridge

William Henry Beveridge, 1st Baron Beveridge, (5 March 1879 – 16 March 1963) was a British economist and Liberal politician who was a progressive and social reformer who played a central role in designing the British welfare state. His 194 ...

and John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in ...

; Fabian socialists such as the Irish author George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

The idea of "genius" and "talent" is also considered by

The idea of "genius" and "talent" is also considered by

In the first half of the 20th century, this led to policies and legislation that resulted in the removal of children from their tribe.

The stated aim was to culturally assimilate mixed-descent people into contemporary Australian society. In all states and territories legislation was passed in the early years of the 20th century which gave Aboriginal protectors guardianship rights over Aborigines up to the age of sixteen or twenty-one. Policemen or other agents of the state (such as Aboriginal Protection Officers), were given the power to locate and transfer babies and children of mixed descent from their communities into institutions. In these Australian states and territories, half-caste institutions (both government or

In the first half of the 20th century, this led to policies and legislation that resulted in the removal of children from their tribe.

The stated aim was to culturally assimilate mixed-descent people into contemporary Australian society. In all states and territories legislation was passed in the early years of the 20th century which gave Aboriginal protectors guardianship rights over Aborigines up to the age of sixteen or twenty-one. Policemen or other agents of the state (such as Aboriginal Protection Officers), were given the power to locate and transfer babies and children of mixed descent from their communities into institutions. In these Australian states and territories, half-caste institutions (both government or

The idea of Social Darwinism was widespread among

The idea of Social Darwinism was widespread among

"the systematic state-sponsored killing of six million Jewish men, women, and children and millions of others by Nazi Germany and its collaborators during World War II ... The Nazis also singled out the Roma (Gypsies). They were the only other group that the Nazis systematically killed in gas chambers alongside the Jews." The scope and coercion involved in the German eugenics programs along with a strong use of the rhetoric of eugenics and so-called "racial science" throughout the regime created an indelible cultural association between eugenics and the

German colonies in Africa from 1885 to 1918 included

German colonies in Africa from 1885 to 1918 included

Beginning in the late 1920s, greater appreciation of the difficulty of predicting characteristics of offspring from their heredity, and scientists' recognition of the inadequacy of simplistic theories of eugenics, undermined whatever scientific basis had been ascribed to the social movement. As the

Beginning in the late 1920s, greater appreciation of the difficulty of predicting characteristics of offspring from their heredity, and scientists' recognition of the inadequacy of simplistic theories of eugenics, undermined whatever scientific basis had been ascribed to the social movement. As the

Maxwell J. Mehlman, Will Directed Evolution Destroy Humanity, and If So, What Can We Do About It?, 3 St. Louis U.J. Health L. & Pol'y 93, 120 (2009).

Eugenics Archive – Historical Material on the Eugenics Movement

(funded by the

University of Virginia Historical Collections: Eugenics"Deadly Medicine: Creating the Master Race"

(United States Holocaust Memorial Museum exhibit)

"Controlling Heredity: The American Eugenics Crusade, 1870–1940"

exhibit at the

"Eugenics"

– National Reference Center for Bioethics Literature Scope Note 28, features overview of eugenics history and annotated bibliography of historical literature

1907 Indiana Eugenics LawThe Fertility of the Unfit

W.A. Chappel, 1903

Mental Defectives and Sexual Offenders

NZ Committee of inquiry, 1925 {{DEFAULTSORT:History of eugenics Eugenics Applied genetics

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Havelock Ellis

Henry Havelock Ellis (2 February 1859 – 8 July 1939) was an English physician, eugenicist, writer, progressive intellectual and social reformer who studied human sexuality. He co-wrote the first medical textbook in English on homosexuality in ...

, Beatrice Webb

Martha Beatrice Webb, Baroness Passfield, (née Potter; 22 January 1858 – 30 April 1943) was an English sociologist, economist, socialist, labour historian and social reformer. It was Webb who coined the term ''collective bargaining''. She ...

and Sidney Webb

Sidney James Webb, 1st Baron Passfield, (13 July 1859 – 13 October 1947) was a British socialist, economist and reformer, who co-founded the London School of Economics. He was an early member of the Fabian Society in 1884, joining, like Geo ...

and other literary figures such as D. H. Lawrence

David Herbert Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English writer, novelist, poet and essayist. His works reflect on modernity, industrialization, sexuality, emotional health, vitality, spontaneity and instinct. His best-k ...

; and Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

such as the future Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

and Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As F ...

. The influential economist John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in ...

was a prominent supporter of eugenics, serving as Director of the British Eugenics Society

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

, and writing that eugenics is "the most important, significant and, I would add, genuine branch of sociology which exists".

Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton, FRS FRAI (; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911), was an English Victorian era polymath: a statistician, sociologist, psychologist, anthropologist, tropical explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist, proto- ...

explained during a lecture in 1901 the groupings which are shown in the opening figure and indicated the proportion of society falling into each group, along with their perceived genetic worth. Galton suggested that negative eugenics (i.e. an attempt to prevent them from bearing offspring) should be applied only to those in the lowest social group (the "Undesirables"), while positive eugenics applied to the higher classes. However, he appreciated the worth of the higher working classes to society and industry.

The 1913 Mental Deficiency Act proposed the mass segregation of the "feeble minded" from the rest of society. Sterilisation programmes were never legalised, although some were carried out in private upon the mentally ill by clinicians who were in favour of a more widespread eugenics plan. The Act, however, enabled the formation of residential schools for the "feeble minded" by social workers such as Mary Dendy

Mary Dendy (28 January 1855 – 9 May 1933) was a promoter of residential schools for mentally handicapped people, i.e. institutionalisation. Dendy was the driving force that established a colony for the "feeble-minded". Dendy believed in separate ...

. Indeed, those in support of eugenics shifted their lobbying of Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

from enforced to voluntary sterilization, in the hope of achieving more legal recognition. But leave for the Labour Party Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

Major A. G. Church, to propose a Private Member's Bill

A private member's bill is a bill (proposed law) introduced into a legislature by a legislator who is not acting on behalf of the executive branch. The designation "private member's bill" is used in most Westminster system jurisdictions, in whi ...

in 1931, which would legalise the operation for voluntary sterilization, was rejected by 167 votes to 89. The limited popularity of eugenics in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

was reflected by the fact that only two universities established courses in this field (University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

and Liverpool University

, mottoeng = These days of peace foster learning

, established = 1881 – University College Liverpool1884 – affiliated to the federal Victoria Universityhttp://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukla/2004/4 University of Manchester Act 200 ...

). The Galton Institute The Adelphi Genetics Forum is a non-profit learned society based in the United Kingdom. Its aims are "to promote the public understanding of human heredity and to facilitate informed debate about the ethical issues raised by advances in reproductive ...

, affiliated to UCL, was headed by Galton's protégé, Karl Pearson

Karl Pearson (; born Carl Pearson; 27 March 1857 – 27 April 1936) was an English mathematician and biostatistician. He has been credited with establishing the discipline of mathematical statistics. He founded the world's first university st ...

.

In 2008, the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative supremacy ...

passed a law prohibiting couples from choosing deaf

Deafness has varying definitions in cultural and medical contexts. In medical contexts, the meaning of deafness is hearing loss that precludes a person from understanding spoken language, an Audiology, audiological condition. In this context it ...

and disabled embryo

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male spe ...

s for implantation.

United States

One of the earliest modern advocates of eugenics (before it was labeled as such) wasAlexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell (, born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born inventor, scientist and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He also co-founded the American Telephone and Te ...

. In 1881 Bell investigated the rate of deafness on Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

. From this he concluded that deafness

Deafness has varying definitions in cultural and medical contexts. In medical contexts, the meaning of deafness is hearing loss that precludes a person from understanding spoken language, an audiological condition. In this context it is written ...

was hereditary in nature and, through noting that congenitally deaf parents were more likely to produce deaf children, tentatively suggested that couples where both were deaf should not marry, in his lecture ''Memoir upon the formation of a deaf variety of the human race'' presented to the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

on 13 November 1883. However, it was his hobby of livestock breeding which led to his appointment to biologist David Starr Jordan

David Starr Jordan (January 19, 1851 – September 19, 1931) was the founding president of Stanford University, serving from 1891 to 1913. He was an ichthyologist during his research career. Prior to serving as president of Stanford Univer ...

's Committee on Eugenics, under the auspices of the American Breeders' Association (ABA). The committee unequivocally extended the principle to humans.

Another scientist considered the "father of the American eugenics movement" was Charles Benedict Davenport. In 1904 he secured funding for the Station for Experimental Evolution, later renamed the Carnegie Department of Genetics. It was also around that time that Davenport became actively involved with the ABA. This led to Davenport's first eugenics text, "The science of human improvement by better breeding", one of the first papers to connect agriculture and human heredity. Davenport later went on to set up a Eugenics Record Office (ERO), collecting hundreds of thousands of medical histories from Americans, which many considered to have a racist and anti-immigration agenda. Davenport and his views were supported at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) is a private, non-profit institution with research programs focusing on cancer, neuroscience, plant biology, genomics, and quantitative biology.

It is one of 68 institutions supported by the Cancer Centers ...

as late as 1963, when his views began to be de-emphasized.

As the science continued in the 20th century, researchers interested in familial mental disorders conducted a number of studies to document the heritability of such illnesses as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. Their findings were used by the eugenics movement as proof for its cause. State laws were written in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to prohibit marriage and force sterilization of the mentally ill in order to prevent the "passing on" of mental illness to the next generation. These laws were upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1927 and were not abolished until the mid-20th century. All in all, 60,000 Americans were sterilized.

Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

became the first state to introduce a compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, is a government-mandated program to involuntarily sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's capacity to reproduce, and is usually done throug ...

bill on May 16, 1897. However, the law did not pass. The proposed law, which called for the mandatory castration of defined types of criminals and "degenerates," fails to pass in the legislature but sets a precedent for similar laws. In 1907 Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

became the first of more than thirty states to adopt legislation aimed at compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, is a government-mandated program to involuntarily sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's capacity to reproduce, and is usually done throug ...

of certain individuals. Although the law was overturned by the Indiana Supreme Court

The Indiana Supreme Court, established by Article 7 of the Indiana Constitution, is the highest judicial authority in the state of Indiana. Located in Indianapolis, Indiana, Indianapolis, the Court's chambers are in the north wing of the Indiana ...

in 1921, the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

upheld the constitutionality of a Virginia law

The law of Virginia consists of several levels of legal rules, including constitutional, statutory, regulatory, case law, and local laws. The ''Code of Virginia'' contains the codified legislation that define the general statutory laws for the Com ...

allowing for the compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, is a government-mandated program to involuntarily sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's capacity to reproduce, and is usually done throug ...

of patients of state mental institutions in 1927.

Beginning with Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

in 1896, many states enacted marriage laws with eugenic criteria, prohibiting anyone who was "epileptic, imbecile

The term ''imbecile'' was once used by psychiatrists to denote a category of people with moderate to severe intellectual disability, as well as a type of criminal.Fernald, Walter E. (1912). ''The imbecile with criminal instincts.'' Fourth editi ...

or feeble-minded

The term feeble-minded was used from the late 19th century in Europe, the United States and Australasia for disorders later referred to as illnesses or deficiencies of the mind.

At the time, ''mental deficiency'' encompassed all degrees of educa ...

" from marrying. In 1898 Charles B. Davenport

Charles Benedict Davenport (June 1, 1866 – February 18, 1944) was a biologist and eugenicist influential in the American eugenics movement.

Early life and education

Davenport was born in Stamford, Connecticut, to Amzi Benedict Davenport, a ...

, a prominent American biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual Cell (biology), cell, a multicellular organism, or a Community (ecology), community of Biological inter ...

, began as director of a biological research station based in Cold Spring Harbor where he experimented with evolution in plants and animals. In 1904 Davenport received funds from the Carnegie Institution

The Carnegie Institution of Washington (the organization's legal name), known also for public purposes as the Carnegie Institution for Science (CIS), is an organization in the United States established to fund and perform scientific research. Th ...

to found the Station for Experimental Evolution. The Eugenics Record Office

The Eugenics Record Office (ERO), located in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, United States, was a research institute that gathered biological and social information about the American population, serving as a center for eugenics and human heredity ...

(ERO) opened in 1910 while Davenport and Harry H. Laughlin began to promote eugenics.

W. E. B. Du Bois maintained the basic principle of eugenics: that different persons have different inborn characteristics that make them more or less suited for specific kinds of employment, and that by encouraging the most talented members of all races to procreate would better the "stocks" of humanity.

The Immigration Restriction League

The Immigration Restriction League was an American nativist and anti-immigration organization founded by Charles Warren, Robert DeCourcy Ward, and Prescott F. Hall in 1894. According to Erika Lee, in 1894 the old stock Yankee upper-class founder ...

(founded in 1894) was the first American entity associated officially with eugenics. The League sought to bar what it considered dysgenic members of certain races from entering America and diluting what it saw as the superior American racial stock through procreation. They lobbied for a literacy test

A literacy test assesses a person's literacy skills: their ability to read and write have been administered by various governments, particularly to immigrants. In the United States, between the 1850s and 1960s, literacy tests were administered t ...

for immigrants

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, and ...

, based on the belief that literacy rates were low among "inferior races". Literacy test bills were vetoed by President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

in 1897 and by President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

in 1913 and 1915; eventually, President Wilson's second veto was overruled by Congress in 1917. Membership in the League included: A. Lawrence Lowell

Abbott Lawrence Lowell (December 13, 1856 – January 6, 1943) was an American educator and legal scholar. He was President of Harvard University from 1909 to 1933.

With an "aristocratic sense of mission and self-certainty," Lowell cut a large f ...

, president of Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

, William DeWitt Hyde, president of Bowdoin College

Bowdoin College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Brunswick, Maine. When Bowdoin was chartered in 1794, Maine was still a part of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The college offers 34 majors and 36 minors, as well as several joint eng ...

, James T. Young, director of Wharton School

The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania ( ; also known as Wharton Business School, the Wharton School, Penn Wharton, and Wharton) is the business school of the University of Pennsylvania, a private Ivy League research university in P ...

, and David Starr Jordan

David Starr Jordan (January 19, 1851 – September 19, 1931) was the founding president of Stanford University, serving from 1891 to 1913. He was an ichthyologist during his research career. Prior to serving as president of Stanford Univer ...

, president of Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is consider ...

. The League allied themselves with the American Breeder's Association to gain influence and further its goals and in 1909 established a eugenics committee chaired by David Starr Jordan with members Charles Davenport, Alexander Graham Bell, Vernon Kellogg, Luther Burbank

Luther Burbank (March 7, 1849 – April 11, 1926) was an American botanist, horticulturist and pioneer in agricultural science.

He developed more than 800 strains and varieties of plants over his 55-year career. Burbank's varied creations inc ...

, William Earnest Castle, Adolf Meyer, H. J. Webber and Friedrich Woods. The ABA's immigration legislation committee, formed in 1911 and headed by League's founder Prescott F. Hall, formalized the committee's already strong relationship with the Immigration Restriction League.

In years to come, the ERO collected a mass of family pedigrees and concluded that those who were unfit came from economically and socially poor backgrounds. Eugenicists such as Davenport, the psychologist

A psychologist is a professional who practices psychology and studies mental states, perceptual, cognitive, emotional, and social processes and behavior. Their work often involves the experimentation, observation, and interpretation of how indi ...

Henry H. Goddard

Henry Herbert Goddard (August 14, 1866 – June 18, 1957) was a prominent American psychologist, eugenicist, and segregationist during the early 20th century. He is known especially for his 1912 work '' The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Her ...

and the conservationist Madison Grant

Madison Grant (November 19, 1865 – May 30, 1937) was an American lawyer, zoologist, anthropologist, and writer known primarily for his work as a eugenicist and conservationist, and as an advocate of scientific racism. Grant is less noted f ...

(all well respected in their time) began to lobby for various solutions to the problem of the "unfit". (Davenport favored immigration restriction and sterilization as primary methods; Goddard favored segregation in his ''The Kallikak Family

''The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeble-Mindedness'' was a 1912 book by the American psychologist and eugenicist Henry H. Goddard, dedicated to his patron Samuel Simeon Fels. Supposedly an extended case study of Goddard’s for ...

''; Grant favored all of the above and more, even entertaining the idea of extermination.) Though their methodology and research methods are now understood as highly flawed, at the time this was seen as legitimate scientific research. It did, however, have scientific detractors (notably, Thomas Hunt Morgan

Thomas Hunt Morgan (September 25, 1866 – December 4, 1945) was an American evolutionary biologist, geneticist, embryologist, and science author who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933 for discoveries elucidating the role tha ...

, one of the few Mendelians to explicitly criticize eugenics), though most of these focused more on what they considered the crude methodology of eugenicists, and the characterization of almost every human characteristic as being hereditary, rather than the idea of eugenics itself.

Some states sterilized "imbeciles" for much of the 20th century. The U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

ruled in the 1927 ''Buck v. Bell

''Buck v. Bell'', 274 U.S. 200 (1927), is a decision of the United States Supreme Court, written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., in which the Court ruled that a state statute permitting compulsory sterilization of the unfit, including th ...

'' case that the state of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

could sterilize individuals under the Virginia Sterilization Act of 1924

The Virginia Sterilization Act of 1924 was a U.S. state law in Virginia for the sterilization of institutionalized persons "afflicted with hereditary forms of insanity that are recurrent, idiocy, imbecility, feeble-mindedness or epilepsy”. It ...

. The most significant era of eugenic sterilization

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, is a government-mandated program to Involuntary treatment, involuntarily Sterilization (medicine), sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's ca ...

was between 1907 and 1963, when over 64,000 individuals were forcibly sterilized under eugenics legislation in the United States. A favorable report on the results of sterilization in California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, the state with the most sterilizations by far, was published in book form by the biologist Paul Popenoe

Paul Bowman Popenoe (October 16, 1888 – June 19, 1979) was an American agricultural explorer and eugenicist. He was an influential advocate of the compulsory sterilization of mentally ill people and people with mental disabilities, and the fa ...

and was widely cited by the Nazi government as evidence that wide-reaching sterilization programs were feasible and humane.

Such legislation was passed in the U.S. because of widespread public acceptance of the eugenics movement, spearheaded by efforts of progressive reformers. Over 19 million people attended the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

, open for 10 months from February 20 to December 4, 1915. The PPIE was a fair devoted to extolling the virtues of a rapidly progressing nation, featuring new developments in science, agriculture, manufacturing and technology. A subject that received a large amount of time and space was that of the developments concerning health and disease, particularly the areas of tropical medicine and race betterment (tropical medicine being the combined study of bacteriology Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the identification, classificat ...

, parasitology

Parasitology is the study of parasites, their hosts, and the relationship between them. As a biological discipline, the scope of parasitology is not determined by the organism or environment in question but by their way of life. This means it fo ...

and entomology

Entomology () is the science, scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such ...

while racial betterment being the promotion of eugenic studies). Having these areas so closely intertwined, it seemed that they were both categorized in the main theme of the fair, the advancement of civilization. Thus in the public eye, the seemingly contradictory areas of study were both represented under progressive banners of improvement and were made to seem like plausible courses of action to better American society.

The state of California was at the vanguard of the American eugenics movement, performing about 20,000 sterilizations or one-third of the 60,000 nationwide from 1909 up until the 1960s. By 1910, there was a large and dynamic network of scientists, reformers and professionals engaged in national eugenics projects and actively promoting eugenic legislation. The American Breeder's Association was the first eugenic body in the U.S., established in 1906 under the direction of biologist Charles B. Davenport. The ABA was formed specifically to "investigate and report on heredity in the human race, and emphasize the value of superior blood and the menace to society of inferior blood". Membership included Alexander Graham Bell, Stanford president David Starr Jordan and Luther Burbank.

When Nazi administrators went on trial for war crimes in Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, they attempted to justify the mass sterilizations (over 450,000 in less than a decade) by citing the United States as their inspiration.The connections between U.S. and Nazi eugenicists is discussed in , as well as . Stefan Kühl's work, ''The Nazi connection: Eugenics, American racism, and German National Socialism'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), is considered the standard scholarly work on the subject. The Nazis had claimed American eugenicists inspired and supported Hitler's racial purification laws, and failed to understand the connection between those policies and the eventual genocide of the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

.

The idea of "genius" and "talent" is also considered by

The idea of "genius" and "talent" is also considered by William Graham Sumner

William Graham Sumner (October 30, 1840 – April 12, 1910) was an American clergyman, social scientist, and classical liberal. He taught social sciences at Yale University—where he held the nation's first professorship in sociology—and be ...

, a founder of the American Sociological Society (now called the American Sociological Association

The American Sociological Association (ASA) is a non-profit organization dedicated to advancing the discipline and profession of sociology. Founded in December 1905 as the American Sociological Society at Johns Hopkins University by a group of fif ...

). He maintained that if the government did not meddle with the social policy of ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups. ...

'', a class of genius would rise to the top of the system of social stratification

Social stratification refers to a society's categorization of its people into groups based on socioeconomic factors like wealth, income, race, education, ethnicity, gender, occupation, social status, or derived power (social and political). As ...

, followed by a class of talent. Most of the rest of society would fit into the class of mediocrity. Those who were considered to be defective ( mentally delayed, handicapped

Disability is the experience of any condition that makes it more difficult for a person to do certain activities or have equitable access within a given society. Disabilities may be cognitive, developmental, intellectual, mental, physical, se ...

, etc.) had a negative effect on social progress by draining off necessary resources. They should be left on their own to sink or swim. But those in the class of delinquent (criminals, deviants, etc.) should be eliminated from society ("Folkways", 1907).

However, methods of eugenics were applied to reformulate more restrictive definitions of white racial purity in existing state laws banning interracial marriage

Interracial marriage is a marriage involving spouses who belong to different races or racialized ethnicities.

In the past, such marriages were outlawed in the United States, Nazi Germany and apartheid-era South Africa as miscegenation. In 19 ...

: the so-called anti-miscegenation laws

Anti-miscegenation laws or miscegenation laws are laws that enforce racial segregation at the level of marriage and intimate relationships by criminalization, criminalizing interracial marriage and sometimes also sex between members of different R ...

. The most famous example of the influence of eugenics and its emphasis on strict racial segregation on such "anti-miscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is the interbreeding of people who are considered to be members of different races. The word, now usually considered pejorative, is derived from a combination of the Latin terms ''miscere'' ("to mix") and ''genus'' ("race") ...

" legislation was Virginia's Racial Integrity Act of 1924

In 1924, the Virginia General Assembly enacted the Racial Integrity Act. The act reinforced racial segregation by prohibiting interracial marriage and classifying as "white" a person "who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian ...

. The U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

overturned this law in 1967 in Loving v. Virginia

''Loving v. Virginia'', 388 U.S. 1 (1967), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark civil rights decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States, laws ban ...

, and declared anti-miscegenation laws unconstitutional.

With the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from the Eastern ...

, eugenicists for the first time played an important role in the Congressional debate as expert advisers on the threat of "inferior stock" from eastern and southern Europe. While eugenicists did support the act, they were also backed by many labor unions. The new act, inspired by the eugenic belief in the racial superiority of "old stock" white Americans as members of the "Nordic race

The Nordic race was a racial concept which originated in 19th century anthropology. It was considered a race or one of the putative sub-races into which some late-19th to mid-20th century anthropologists divided the Caucasian race, claiming th ...

" (a form of white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

), strengthened the position of existing laws prohibiting race-mixing. Eugenic considerations also lay behind the adoption of incest

Incest ( ) is human sexual activity between family members or close relatives. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by affinity (marriage or stepfamily), adoption ...

laws in much of the U.S. and were used to justify many anti-miscegenation laws

Anti-miscegenation laws or miscegenation laws are laws that enforce racial segregation at the level of marriage and intimate relationships by criminalization, criminalizing interracial marriage and sometimes also sex between members of different R ...

.

Stephen Jay Gould

Stephen Jay Gould (; September 10, 1941 – May 20, 2002) was an American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely read authors of popular science of his generation. Gould sp ...

asserted that restrictions on immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, and ...

passed in the United States during the 1920s (and overhauled in 1965 with the Immigration and Nationality Act The U.S. Immigration and Nationality Act may refer to one of several acts including:

* Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952

* Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965

* Immigration Act of 1990

See also

* List of United States immigration legisla ...

) were motivated by the goals of eugenics. During the early 20th century, the United States and Canada began to receive far higher numbers of Southern and Eastern European immigrants. It has been argued that this stirred both Canada and the United States into passing laws creating a hierarchy of nationalities, rating them from the most desirable Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

and Nordic peoples to the Chinese and Japanese immigrants, who were almost completely banned from entering the country. Others, however, argued that Congress gave virtually no consideration to these factors, and claim the restrictions were motivated primarily by a desire to maintain the country's cultural integrity against the heavy influx of foreigners.

In the US, eugenic supporters included Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, Research was funded by distinguished philanthropies and carried out at prestigious universities. It was taught in college and high school classrooms. Margaret Sanger

Margaret Higgins Sanger (born Margaret Louise Higgins; September 14, 1879September 6, 1966), also known as Margaret Sanger Slee, was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger popularized the term "birth control ...

founded Planned Parenthood of America to urge the legalization of contraception

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

for poor, immigrant women. In its time eugenics was touted by some as scientific and progressive, the natural application of knowledge about breeding to the arena of human life. Before the realization of death camps

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the idea that eugenics would lead to genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Latin ...

was not taken seriously by the average American.

Australia

The policy of removing mixed-race Aboriginal children from their parents emerged from an opinion based on Eugenics theory in late 19th and early 20th centuryAustralia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

that the 'full-blood' tribal

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to conflic ...

Aborigine would be unable to sustain itself, and was doomed to inevitable extinction, as at the time huge numbers of aborigines were in fact dying out, from diseases caught from European settlers.Russell McGregor, ''Imagined Destinies. Aboriginal Australians and the Doomed Race Theory, 1880–1939'', Melbourne: MUP, 1997 An ideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied pri ...

at the time held that mankind could be divided into a civilizational hierarchy. This notion supposed that Northern Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

ans were superior in civilization and that Aborigines were inferior. According to this view, the increasing numbers of mixed-descent children in Australia, labeled as "half-castes" (or alternatively "crossbreeds", "quadroons", and "octoroons") should develop within their respective communities, white or aboriginal, according to their dominant parentage.

In the first half of the 20th century, this led to policies and legislation that resulted in the removal of children from their tribe.